The farmers and ranchers of the Dakotas are ahead of environmentalists on preserving the prairie and fighting global warming.

The first night of my visit to North Dakota Brad Crabtree fed me a hearty steak dinner-courtesy of a steer he’d recently sent to the butcher. In later days, we feasted on hamburgers, sausage, and leg of lamb. Brad had killed and butchered the lamb himself a few weeks earlier, chopping it up on the same kitchen table where we later had dinner.

The first night of my visit to North Dakota Brad Crabtree fed me a hearty steak dinner-courtesy of a steer he’d recently sent to the butcher. In later days, we feasted on hamburgers, sausage, and leg of lamb. Brad had killed and butchered the lamb himself a few weeks earlier, chopping it up on the same kitchen table where we later had dinner.

Years before when I had visited Brad and his wife Renee, dinner consisted of tofu, bean sprouts, and lentils. They were both vegetarians, and Brad was working on environmental policy reform in Washington n” DC. In 1997, they grew tired of DC and moved to Brad’s native North Dakota. Renee gave birth to a daughte4 and they bought a farmstead in the Missouri Couteau-a windswept stretch of rolling green hills and scattered small lakes in the central part of the state. There they built the most eco- friendly farmhouse possible. Its wooden frame is made from timber that blew down in a windstorm and boards salvaged from old barns. The walls are of baled straw cut from the stubble left after the alfalfa harvest.

Brad is now a consultant for the Minneapolis-based Great Plains Institute for Sustainable Development, which runs educational and policy programs to help rural communities develop economically while protecting the environment. But Brad isn’t just working with the agricultural sector; he’s working in it. Two years ago he began ranching cows and sheep on his land, a decision that clearly marks his departure from the mainstream environmental community. “Where the environmental movement has gone wrong is on grazing,” says Brad, speaking now as an outsider. “They are in the early medieval phase of resource management.” He acknowledges that traditional ranching can do a great deal of harm, but he insists that well-managed grazing can benefit the environment by using cows and sheep to fill the role that buffalo once played in the prairie ecosystem.

Brad and Renee’s wind-powered, sustainably grazed ranch is not an isolated, idealist experiment. It’s a small example of a growing movement to transform the Northern Plains. And it is led not by environmentalist dreamers but by practical ranchers and farmers who want to make money.

Eat a steak, save the earth

One of those ranchers is Gene Goven. In a business where traditional family operations are crushed under debt and competition from subsidized agribusinesses, Gene’s ranch is relatively prosperous thanks to his different way of looking at things.

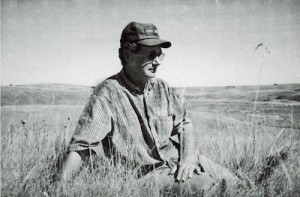

A soft-spoken, middle-aged man who wears a base- ball cap instead of a Stetson; Gene didn’t set out to be a land management expert. He was just trying to make a living on the ranch-originally a homesteader plot-that inherited from his father in 1967. At first, he ran cattle the same way everyone else did-by putting a single fence around the land and letting the cows roam where they would. The cattle overgrazed the spot by the lakeshore that had the nicest grass, while the rest of the land became overgrown- a preference Gene likens to people at a salad bar picking out the tender greens and leaving the tough, chewy lettuce.

Gene watched helplessly for years, until he got an idea. He built a fence around the overgrazed area and forced the cattle onto other parts of the pasture. Over the years, he continued to subdivide his pasture in a process called cross-fencing. Today, he has nineteen mini-pastures that he moves the cattle through on a carefully planned rotation. Each gets one good grazing, then he moves the cows onto another section, allowing the grazed pasture time to regenerate. This practice has paid off handsomely; he realized that his prime resource is not the cows, but the grass.

“I can’t raise any more beef than I have grass to convert into beef,” he explains. “Therefore, I have to be a grass manager first, and a cowboy second.” Gene now focuses entirely on the grass-managing job and leaves the cowboy work to other ranchers who pay to graze cattle on his prime pastureland. So the healthier the prairie, the more cattle he can take and the more money he can charge. In addition, the lush prairie creates a better habitat for wildlife, and Gene now makes extra money off gratuities from people who come to hunt.

While this is all good for business, Gene’s motivations run deeper. “I always did love being on the prairie,” he says as he reclines in the thick grass. “Listen to it. You can hear the insects and the birds.” Later he takes up a handful of humus from the rich soil and sniffs it like a wine connoisseur sampling the bouquet. I asked Gene if he were an environmentalist, and he replied with his own question. “What does the term ‘environmentalist’ mean?” he asked. “If I enjoy being out here, and I want to improve it, does that make me an environmentalist?”

Good intentions, bad decisions

Good intentions, bad decisions

Gene is cautious about labels because mainstream environmentalists often vilify ranchers as opportunists who devastate the landscape with their voracious cattle herds. To most environmentalists, protecting the prairie means keeping it off limits to any development. This is the thinking behind the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), a US Department of Agriculture program that pays farmers and ranchers to idle their land for 10 to 15 years. But the prairies were not idle in their natural state.

Rather, they evolved and thrived under intensive grazing from elk and buffalo. With these species virtually wiped out, Gene sees cows as the best substitute.

His pastures are not only healthier than traditional ranches; they also beat the CRP lands. Without grazing, the prairie suffocates. A few aggressive species choke out many other plant types, so an untouched prairie gradually loses its biodiversity and turns into a depleted patch of weeds. Idle land is further depleted by dead weeds that cover the ground and block out sunlight to other plants. Grazing cattle keep the aggressive plants in check; and by tramping through the prairie; they pack the dead plant material into the soil surface-accelerating its decomposition and the recycling of nutrients for future growth.

The contrast between grazed and idle land can be dramatic. While the CRP parcels in North Dakota have just a handful of plant species, Gene has counted over a hundred varieties on his heavily grazed land. And the differences in animal populations are equally stark. “The aging CRP land is a desert, as far as wildlife is concerned,” says Gene.

He also fears the pro- gram is turning rural com- munities into deserts by encouraging farmers and ranchers to just take the government check and abandon their properties. (The USDA expects to shell out $1.6 billion in CRP payments this year.) But the program survives because it has strong supporters. Banks love the CRP because it provides a more reliable source of income for farmers who are often paying down massive debts. And many environ- mentalists support it because they equate all grazing with overgrazing.

Meanwhile, land stewards like Gene Goven are shaking their heads in disbelief of the perverse incentives. Knowing that his lush prairies provide rich habitat for wildlife, Gene asked the Department of Agriculture if he could enroll some of his land in the CRP. But the inspectors basically told him that his land was to good to qualify. Had he depleted the plant species and triggered massive erosion Gene would have been rewarded with CRP payments to stop him from doing further damage. But because he did everything right, he didn’t get a penny.

Though he couldn’t bring the government to his ranch lands, Gene has brought his ranching techniques to government land. In the mid 1980s, he and a neighbor approached the US Fish and Wildlife Service with a proposal to run livestock on public land as a way of enhancing the habitat. The local USFWS officials opposed it. “We were probably considered crazies back there,” Gene recalls with a chuckle. But the regional director, Dale Henry, thought it might work. He asked Gene to undertake a demonstration project on a barren parcel that had been idle for 20 years, and Gene received the first new grazing permit ever approved for protected USFWS lands. After one year, birds began nesting on the land again, and by the second year ” they really moved in,” says Gene. Today, such prescribed grazing is a standard practice on federal lands throughout the country.

The answer is blowing in the wind

The farmers and ranchers of the Dakotas and neighboring states are also challenging conventional wisdom-and politics-on energy policy. They plan to make the region a center of pollution-free wind and hydrogen power, but they are not doing it to help the environment, at least not primarily. They are doing it for the money.

“I’m not a big fan of green power,” says Jim Nichols-a tall, white-haired county commissioner in western Minnesota-dwarfed beneath a 24O-foot-tall wind turbine. “If you want my view, there’s one great reason for wind energy: It’s cheap!” Nichols is leading a tour of a vast wind farm (461, turbines) on Minnesota’s Buffalo Ridge. The members of the tour have come to Minnesota for a meeting of the Powering the Plains Initiative-a coalition of government, business, and community leaders from North and South Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Manitoba whose goal is to develop at least 10,000 megawatts of new wind power in the region by 2020. The Great Plains Institute for Sustainable Development is coordinating the initiative (together with the North Dakota Consensus Council), and running it is now Brad Crabtree’s biggest project. Powering the Plains includes a few environmentalists, but even they play down the ecological aspects of wind power. “It’s not an environmental thing. We’ve never sold it that way,” says Scot Kelsh a state representative from North Dakota and Director of the state’s Clean Water Action environmental organization. The selling point, instead, is that wind power is a great way to boost the incomes of rural communities, where farmers and ranchers can either raise their own turbines or lease the land to energy companies that develop wind farms.

According to Joe Richardson, who heads a joint wind power initiative for the North Dakota and South Dakota Farm Bureaus, his conservative organizations are now more progressive on pushing wind power than the environmentalists. Acknowledging the role that activists played in getting wind power off the ground twenty years ago, he says “Thank you very much environmentalists. Now get out of our way.”

As an example of how roles have changed, Joe recalls the differing reactions from the Farm Bureau and the environmentalist Union of Concerned Scientists when Senators Byron Dorgan and Kent Conrad of North Dakota voted in favor of a provision in the federal energy bill that would require 10 percent of the nation’s new power generation to come from wind. UCS asked the Farm Bureaus to write a letter of thanks to the senators. “But we said no. We want 20 percent,” recalls Joe, referring to the goal of a defeated amendment offered by Senator Jim Jeffords and not supported by Dorgan and Conrad.

The accidental advocate

While he may not be in the environmental camp, Joe is not a typical member of the conservative Farm Bureau either. A hippie in his college years, Joe has had a variety of careers. In the late 70s,he founded a nonprofit organization, the Plains Distribution Service, that brought writers, poets, and their books to rural communities. After a decade in nonprofit work, Joe went into the gambling business. He started as a pit boss for the blackjack tables at a local steakhouse and went on to found his own school to train blackjack dealers. Then he gambled on business startups. In 2001 he was trying to create a business handling airline reservations, but his plans fell apart after September 11.

On September 15, Joe’s father faxed him a newspaper article about wind power and asked if he should invest in it. Suspecting it would be a boondoggle, Joe began looking for problems, but he couldn’t find any. “The more I dove into it the more I learned that wind power was real” he recalls. “North Dakota had this tremendous resource.” He learned, for instance, that his state is the windiest in America-with the potential to generate about 35 percent of all the electricity consumed in the United States. Add South Dakota, and the figure jumps to 63 percent. And the windiest part of the region is the hill country of the Missouri Couteau where Brad and Renee’s ranch is. On average, the wind sweeps the hills at over 21 miles per hour. Anything above 14 miles per hour is a prime condition for generating electricity. Yet Brad and Renee’s little turbine is one of the few wind generators in the entire state.

In Joe’s vision, every farm in the region should have turbines, and not the thousand-watt “egg beater” type as he joking calls Brad’s windmill but rather six or seven hundred thousand watt generators-each producing enough power for a small town. Along with selling beef or grain to market, Joe wants ranchers and farmers to be selling electricity.

He sees wind as the best opportunity to pull farmers out of debt and revive failing rural communities. (Among US states, North Dakota ranks 48th in average annual wages.) And he was flabbergasted that the North Dakota Farm Bureau didn’t see the same potential. In November 2001, he sent a 17-page policy paper to the bureau with a detailed economic argument for wind power. It also included a call to action for citizens, with an ultimatum:

To my fellow landowners and farmers, insist that the North Dakota Farm Bureau and the American Farm Bureau become actively and publicly engaged as partners in wind development… Send your dues envelopes back without payment or with half payment stating that if they can’t publicly and aggressively support wind power development as an important source of new farm income, then their agenda is not our agenda.

Herb Manig Vice President of the North Dakota Farm Bureau was floored by Joe’s threats. But he was also intrigued by the economic data Joe included. He wrote back to Joe, and after giving a brief lecture on manners, he invited him to meet for lunch. 144’ren Herb got to the restaurant, he discovered that this audacious, tough-talking hell- raiser was, in fact, a dwarf with bushy white hair and big glasses. At five foot one, Joe is rather tall for his condition. “I’m a giant dwarf,” he says with a chuckle. And he had no problem explaining his giant ideas to Herb Manig. “It didn’t take me long to recognize that I was sitting with a genuine genius,” Herb recalls of their first meeting.

Herb took Joe’s ideas to his president and board of directors, a group he describes as “conservative, but pragmatic,” and Joe was hired to head up the Farm Bureau’s pro-wind strategy. For the Farm Bureau, wind power is mainly about helping its members earn extra money, not about helping reduce smog or global warming. But Herb did warn his board that taking on this project would bring them into an alliance with political groups they normally shunned. And he was right: with- in a few months he got a call from Ted Turner’s ultra-liberal foundation, congratulating him on the Farm Bureau’s environmental leadership.

Freedom from carbon

The wind advocates face a lot of obstacles. One is getting power lines built. Like a remote oil field without a pipeline, the wind fields of the Dakotas arc far from the major transmission lines of the regional grid. Building lines would certainly be a worthwhile investment, but regulatory and political roadblocks stand in the way. Another obstacle is the intermittent nature of wind power. The wind never stops in the region, but it does slow down a lot in midwinter and midsummer. Current federal rules penalize generators that cannot provide a steady flow of power. Regulations also make it hard to justify building lines to a power source that isn’t already in place. Wind farms can grow incrementally, as more farmers raise turbines. So the transmission lines would have to be overbuilt, initially, to make room for future growth. Companies much prefer building a single line to a single energy source, like a coal-fired power plant.

And that’s the political barrier.. Most of North Dakota’s power comes from burning the lignite coal that is plentiful in the western part of the state, and70 percent of that power is exported, creating a powerful coal lobby with considerable influence in the state capital. But there’s a chink in the armor-a firm advocate of zero- emission power who happens to work in the coal industry. Basin Electric Power Cooperative is the most carbon- intensive utility in America, producing more carbon dioxide per megawatt than any other generator. However, the company’s vice president, Al Lukes, thinks he can bring the carbon dioxide pollution way down-all the way to zero. Instead of burning the coal outright, it will go into a gasification process that releases hydrogen” the one truly clean fuel. Gasification will produce a lot of carbon dioxide but none of it will make it into the atmosphere: Lukes plans to pump it into abandoned oil wells in Canada.

Hydrogen fuel is not only good for the environment, it’s good for wind power. At times when wind is light hydrogen-burning plants can kick in to maintain a steady flow of power. And in addition to complementing wind power, Basin itself will be getting into the business. In the fall of 2002, the company announced plans to build its own 80 megawatt wind farm. “It’s a genuinely meaningful step that goes beyond PR or legal requirements,’ says Brad Crabtree, noting the size of the project. “If they just wanted good PI! they could have built an eight megawatt facility.” And while other utilities have built larger installations, they have done it because of legal mandates that required them to develop alternative energy.

So, while environmentalists are struggling to get the Bush Administration to even contemplate slight reductions in global warming gases, the largely conservative farmers, ranchers, and coal barons of the Dakotas are making concrete plans for a carbon-free economy.

Green but unseen

Back on the Crabtree ranch many environmentalist absolutisms fall away. From the environmentalist perspective, a field of cows means overgrazing, erosion, and water pollution. But on the Crabtree and Goven ranches, and many more, cows are improving the environment. You can eat a steak and feel you are performing a public service.

And while I was eating my steak or walking the fields or feeding the sheep, the wind kept blowing and the windmill kept turning. One night I forgot to turn a light off. When I noticed it the next morning, I immediately felt guilty-seeing every watt as another puff of car- bon dioxide thickening our heat-trapping atmosphere. But no coal or gas was burned to light this lamp. The wind simply blew, like it always does. The lamp shone because of nature, not in spite of it.