While covering an Occupy Wall Street planing meeting about a month ago, I learned that the professor sitting next to me was helping coordinate with protestors in other countries.

While covering an Occupy Wall Street planing meeting about a month ago, I learned that the professor sitting next to me was helping coordinate with protestors in other countries.

“I’d love to talk to you about that,” I said.

“Great, can you help us out?”

“Oh I can’t get involved,” I explained. “I have to stay objective.”

“I don’t understand that,” he replied.

My impulse was to lecture him about the importance of objectivity in journalism, that journalists taking a stance threatens the public’s ability to learn the real truth without spin. Truthfully, the remark angered me.

But had I engaged with him like that, I would have given up the very objectivity I meant to to defend.

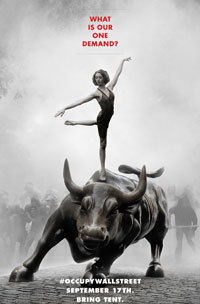

My involvement – and later the involvement of many journalists – in covering the #OccupyWallStreet protests surfaces a great debate and possible hazard in journalism – becoming part of the story.

I thought about this when I read of the arrest of Times contributor Natasha Lennard. With that action, she’s becoming part of the narrative. (I have no idea if she has a personal stand in this protest. Her arrest simply got me thinking.)

I felt the same change on day one when my reports got largely retweeted, as I was probably the first journalist reporting from inside the march (as well as the first to attend the very earliest planning meetings).

It’s also hard when trying to convince editors of the importance of a story. In making a case for covering it, you sound a little like an advocate.

Everyone (certainly the OWS protestors, from what I’ve heard them say) expects the media to have an agenda. Understandable, since it so often does.

That’s not our job. Of course I have opinions, and some of my friends and family know them. But the more I report, the less strong they become.

Why?

I’m more excited and driven by diligent objectivity than by taking sides.

It’s what I do. Protestors take stands. Journalists (should) inform the public about those stands without spin.